Mr. Fullington

By Stephen Minister, PhD

Scripture passage: Matthew 8:1-3

When I first met Mr. Fullington, he was listening to a cricket match on the radio. Mr. Fullington lived in Guyana—a small country on the northern coast of South America, that had once been a part of the British Empire. Because of this, cricket is the national sport, and Mr. Fullington spoke English with a regal British accent. He carried himself with an air of dignity, or even distinction, which was enhanced by the fact that nobody ever called him by his first name; even people who had known him for a long time still referred to him as Mr. Fullington. And, of course, he showed us hospitality by serving us afternoon tea. While we drank our tea, he explained the rules of cricket to us, but please don’t ask me to repeat them as I never fully understood the game.

More memorably, Mr. Fullington regaled us with stories from his years as a diamond miner in the jungles of Guyana. He even told us the secret to finding diamonds in the jungle caves, though at first we misunderstood. We thought he said that you needed to look around the cave for a ratchet. For a few minutes we were thoroughly perplexed—why were there ratchets in remote caves? How did they get there? And what did ratchets have to do with finding diamonds? Eventually, we realized that we had misunderstood him, both because of his accent and his gentlemanly demeanor. He hadn’t said the word ‘ratchet,’ but instead had used a two-word phrase for rodent feces. To this day, I don’t know why rodent feces indicates the presence of diamonds, but I have it on Mr. Fullington’s authority that rodent feces is the key.

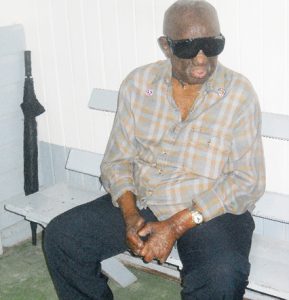

Though I now think of Mr. Fullington with fondness and respect, I must confess that before I met him, I was filled with trepidation. And, in fact, when we came face-to-face and he stretched out his hand to shake mine, I had a moment of hesitation. I hesitated because I didn’t see his dignity, his hospitality, his rich life experience—in a word, his humanity. Instead, I only saw the one thing I knew about him before we met: I saw only his leprosy. Somewhere in the jungles of Guyana, Mr. Fullington had contracted leprosy, or what doctors now call “Hansen’s disease.” Hansen’s disease is an infection that can damage the nerves, eyes, skin, and respiratory tract. Because of the nerve damage, people with Hansen’s disease may not realize when they have a cut or wound. This can allow the wound to get infected and the infection to spread, leading to the loss of certain body parts.

So, when I met Mr. Fullington, he was missing most of his fingers and was blind in both eyes. He lived in what was called a “leprosy hospital,” but was clearly more focused on exclusion than care. It was a small compound an hour from the nearest town, completely surrounded by a tall fence to keep the people with leprosy in and everyone else out. On this compound, Mr. Fullington and others were warehoused in a large, dilapidated hall, sectioned off into 8’x8’ plywood rooms. All this despite the fact that they weren’t even contagious. Mr. Fullington, like all the residents, was taking medicine that kept the disease from spreading to others. On top of that, 95% of humans have a

genetic immunity that prevents them from getting Hansen’s disease anyway. I knew all that when I met Mr. Fullington, and yet I hesitated anyway because I saw only his disease, and I was afraid.

In the passage from Matthew, Jesus responds in a very different way to the man with leprosy. Jesus surely knew nothing about genetic immunity and the man with leprosy surely wasn’t taking medicine to prevent the spread of the disease. And yet, Jesus nonetheless reaches out & touches him. At the time, leprosy wasn’t just a debilitating disease, but also carried a social stigma. People with leprosy were forced to live outside cities, deprived of job opportunities and the ability to participate in society. And religious ideology backed this up, claiming that leprosy was a punishment from God because of people’s sinfulness. Rather than love of neighbor, this religious doctrine was used to justify discrimination against people who had done nothing wrong. And yet, when the man with leprosy calls to Jesus, Jesus doesn’t see the social stigma. And he doesn’t, like me, see only the physical disease. Jesus sees the man’s humanity, his dignity—and so Jesus reaches out and touches him.

What we see first about people disproportionately shapes how we think about them. For example, let me tell you about two fictitious people: Emily and Anna. Emily is intelligent, industrious, critical, stubborn, and envious. And, Anna is envious, stubborn, critical, industrious, and intelligent. Do you have a more favorable impression of Emily? If so, you’re not alone. This example comes from a research study that found that people had much more positive views of Emily than Anna, despite the fact that the five adjectives used to describe them are exactly the same. The only difference is the order they’re given in. Emily’s description starts with the positive adjectives—intelligent and industrious—and so people have a more positive view of her than Anna, whose description starts with the negative adjectives—envious and stubborn. What we see first when we encounter someone matters because it shapes how we think about them, and so how we treat them.

So what should we see first when we encounter others? In thinking about this question, I thought of the way we begin the call to worship every Sunday: “the god in me greets the god in everyone of you, Namaste. Namaste, the spirit in me meets the same spirit in you.” Namaste is an ancient Hindu greeting meaning something like, “the sacred in me recognizes the sacred in you.” Similar to the way the Jewish and Christian traditions regard everyone as being made in the image of God, Hinduism holds that the divine is present in every person. And so, even today the customary way of greeting someone in India is to say “Namaste,” the sacred in me recognizes the sacred in you. Now I think that’s really cool—that the first thing you say to someone is that you see the sacred in them, you see that they’re made in the image of God.

I love that. And I love that not because it’s easy or obvious to see the image of God in others. Precisely the opposite. It’s easy to see people and immediately categorize, or stereotype, or judge people based on their appearance or social position. And so, I think we need regular reminders that we are to see others as first and foremost made in the image of God—with dignity and humanity—the way that Jesus saw the man with leprosy. Each Sunday, when I say “Namaste, the spirit in me meets the same spirit in you,” I say it not in a triumphant way, not as a sign of some accomplishment at being profound, but as a needed reminder, as a challenge to see the divine in all those I interact with. And especially in those it’s hard for me to see the divine in—the coworker who drives me nuts, the acquaintance who always seems to be complaining, the neighbor who doesn’t seem to have a sense of property lines, Green Bay Packers’ fans. Just kidding about the Packers fans!

In addition to the personal hang-ups that prevent us from seeing the divine in others, contemporary American society is beset with social stereotypes, religious ideologies, and political agendas that attempt to cover over the dignity and humanity of certain people, just as in Jesus’s time people with leprosy suffered from socially-sanctioned discrimination. The effort to portray immigrants as dangerous and criminals—even though they commit crimes at much lower rates than people born in the U.S.—is a clear attempt to deny their dignity and humanity, to get us to see immigrants with fear and suspicion, rather than seeing the image of God in them.

In South Dakota in recent years, there have also been repeated efforts to create fear and suspicion toward people who are transgendered. We’ve been told that trans-people can’t be trusted to honestly describe their own experience, to use public restrooms, or to make their own medical decisions. Claims like these deny to people who are transgendered the dignity and respect that we all deserve. One of the things I deeply value about our church, Spirit of Peace, is that we affirm, in both word and deed, that all are made in the image of God and so worthy of respect, support, and love.

In thinking about these ideas, there’s one other contemporary application that I thought about, one that may be more challenging for some of us. As we all know, this is a time of sharp political polarization in the U.S. The two main political parties have moved farther apart and every issue seems to be fought as if the future of civilization depended on it. I recently saw a study that said that Americans are now much more open to marrying someone from a different religion that someone from a different political party. While that’s good news for religious tolerance, it demonstrates the fear and suspicion we have toward people on the other side of the political aisle. So, here’s the question: can we see the image of God in those we disagree with politically, or do we only see their political affiliation? Do we see them as people with dignity, humanity, and rich, complicated life experience, or do we only see stereotypes of their partisan identity?

Here maybe Jesus is a helpful exemplar as well. Jesus lived in a politically difficult time—under unjust Roman military occupation and with religious authorities who were more interested in their own power and prestige than in loving their neighbors. And so, on the one hand, Jesus publicly taught that the Kingdom of God is radically different than the Kingdom of Rome; but, on the other hand, on a personal level, Jesus also saw the humanity of tax collectors who worked for the Roman Empire and the humanity of a Roman Centurion whose daughter was sick. On the one hand, Jesus denounced the Pharisees is the harshest possible terms, but on the other hand, when the Pharisee Nicodemus comes to Jesus, Jesus treats him with respect and dignity.

As I’ve struggled to figure out how to respond to our political polarization, I wonder if Jesus’s example is a model to follow: standing up to leaders who pursue their own power and prestige, while neglecting those who are suffering and in need; publicly speaking out against injustice and against social norms and practices that marginalize and oppress; and yet still being able to treat those on the other side of the political aisle as human beings, with dignity, made in the image of God. I know for me, that can sometimes be a challenge.

A year and a half ago, Mr. Fullington passed away. When I think about him, I realize that there’s another important difference between Jesus’s encounter with the man with leprosy and my encounter with Mr. Fullington. Whereas Jesus offers healing to the man with leprosy, it was Mr. Fullington who offered me a kind of healing—an opportunity to overcome my own blindness, my inability to see the dignity and humanity in another. Mr. Fullington exploded my narrow-minded, fear-filled stereotypes about him, and in doing so allowed us to connect as humans, allowed the spirit in me to meet the same spirit in him. Seeing the divine in others and reaching out to them affirms their dignity, but it also affirms our own. May it be so for you and for me. Amen.

A year and a half ago, Mr. Fullington passed away. When I think about him, I realize that there’s another important difference between Jesus’s encounter with the man with leprosy and my encounter with Mr. Fullington. Whereas Jesus offers healing to the man with leprosy, it was Mr. Fullington who offered me a kind of healing—an opportunity to overcome my own blindness, my inability to see the dignity and humanity in another. Mr. Fullington exploded my narrow-minded, fear-filled stereotypes about him, and in doing so allowed us to connect as humans, allowed the spirit in me to meet the same spirit in him. Seeing the divine in others and reaching out to them affirms their dignity, but it also affirms our own. May it be so for you and for me. Amen.